In 1995, in the Perm region of the Russian Federation, a unique memorial museum of the history of political repression was created in the former camp for political prisoners Perm-36. The core of this camp is the only surviving camp complex of buildings from Stalin’s gulag era. For nearly 20 years, the Memorial Centre Perm-36 not only preserved and restored the dilapidated camp construction, but was engaged in research, collecting, exposition, exhibition and education activities.

In 2014, with the political changes in Russia and the change of the governor of the Perm region, Memorial Centre Perm-36 was closed and all the buildings and the facilities of the former camp, which are state property, were transferred to establish a state institution that drastically changed the mission of Memorial Centre Perm-36. No longer is the site a museum devoted to the repressive forced-labor practices of the Stalin era, but one that presents the gulag as a vital component of the Soviet victory in World War II.

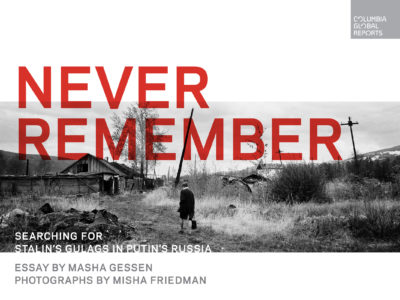

The Coalition continues to work with the original founders of Memorial Centre Perm-36, however, assisting them in enhancing and expanding their work, which is currently focused on the development of a website documenting gulags and sites of detention. We are also pleased to share with you this excerpt from Never Remember: Searching for Stalin’s Gulag’s in Putin’s Russia, a new collection of essays by Masha Gessen with photographs by Misha Friedman. The following is a section from a chapter on Perm-36 that includes the recollections of Sergei Kovaliov, a former inmate there.

Chapter Four

Sergei Kovaliov

What did Perm-36 feel like to an inmate? I asked Sergei Kovaliov, who spent five years there, starting in 1975. He was forty-five when he arrived—an old man by camp measure and by Soviet standards. He overheard two guards talking to each other.

“Why did they put the old guy in here? He seems harmless.”

“He shouldn’t have trashed the Soviet authorities.”

Kovaliov’s anti-Soviet activities, as these things were called, dated back to the 1950s, when, as a young biology Ph.D., he tried to speak up in defense of genetics, a banned science in the Soviet Union. In 1969, he co-founded the first independent human rights organization in the country. In 1971 he co-founded the Chronicles of Current Events, a typewritten underground newsletter that documented human rights abuses. He was arrested in 1974, convicted of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” and sentenced to seven years in a prison camp and three years of internal exile.

His work on the Chronicles had prepared Kovaliov for Perm-36 pretty well: he knew many of the camp rules and the possible penalties for violations. What he did not know was how enforcement worked. Back when he was typing up news items for the Chronicles—often these were about an imprisoned dissident being placed in solitary as punishment for having been unshaven or for having failed to button his prison robe all the way to the top, or having worn his indoor slippers out on the porch, or having tea with a friend in another dormitory—he had sometimes found himself wondering how hard it can be to observe clearly articulated rules, however absurd, and what the point of violating them was, considering the cost. At Perm-36 he found out that no one usually observed most of the tiny nitpicky rules—and the guards paid no attention unless they needed a pretext for placing you in solitary. Then you could be busted, as Kovaliov once was, for having the top button of your robe undone while in the bedroom in the barracks. The whole point of having detailed, excessive rules was to guarantee the option of selective enforcement: If the rules had been applied evenly and consistently, they would not have been very useful as an instrument of control.

Penalties came in two varieties. There was solitary, and there was “confinement to a cell.” Both kinds were administered in a single building a short walk from the dorms. “Confinement to a cell” was a bit easier to take—you got a mattress and a sheet, and you were fed every day. In solitary, food came every other day. That was harder than being on a hunger strike: When you don’t eat at all, you don’t feel hungry, but when you are fed every other day, you are starving most of the time. Solitary, on the other hand, was a short-term penalty, while confinement to a cell could last months. Kovaliov did two six-month stints of confinement to a cell, and he lost count of how many times he was placed in solitary.

Right around the time he lost track of his stays in solitary, he was summoned to the administration building—known grandly as “the headquarters”—and informed that he was incorrigible. This meant confinement to a cell. On his second day in his cell, Kovaliov received a visit from a young, rosy-cheeked captain.

“You probably want to know why you’ve been confined,” said the captain.

“Actually, I had an entire protocol read to me,” said Kovaliov. The protocol contained a litany of his nuisance infractions.

“That’s all nonsense,” said the captain and produced a piece of paper covered in fine, beady script. This was a draft of a letter a group of Perm-36 inmates had sent to a meeting of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, the first such meeting to follow the signing of the Helsinki Accords, in which the Soviet Union had accepted a set of human rights obligations in exchange for trade concessions from the West. The letter said, in part:

We realize that the issue of political prisoners is not the top priority in today’s world, and yet we dare to insist on advancing it, for it goes to the root of a most dangerous epidemic of our century: the tendency of a state to violate its own laws and declarations, using force in violation of both law and morality.

The Helsinki Accords, signed in 1975, contained four parts, which the drafters had called “baskets.” The third of these baskets contained the human rights provisions on which Soviet dissidents could now base their calls for action. The letter continued:

We bear witness to the fact that even after the signing of the Helsinki Accords persecution for dissenting thought continues to be the regime’s main preoccupation. We believe that the West understands, as we do, that the “third basket” is like air and daylight, without which all else loses meaning.…We also hope that people of authority in the West understand that when they choose to seek compromise with forces of militant lawlessness…they accept the responsibility for eroding the ground on which we all stand.

Kovaliov read the piece of paper the captain had handed to him, taking his time to demonstrate that he was seeing it for the first time.

“An excellent piece of writing,” said Kovaliov. “I’d sign this myself.”

“You did,” said the captain.

Kovaliov learned three things from this conversation. One, that the inmate who worked the coal stove in the camp’s heating plant, a Russian nationalist activist widely suspected of being a snitch, was more than a snitch: He had apparently tracked down and managed to extract this draft of the letter from a piece of pipe in the heating room in which the writers had cemented it. Kovaliov was sad to lose the draft, but grateful for the second thing he learned. The letter had apparently reached the addressee, because the captain knew that Kovaliov had signed it. The draft was unsigned, but the version of the letter that had been smuggled out had Kovaliov’s signature first in a list of fourteen inmates.

Kovaliov had smuggled this letter out himself. The inmates called the process “camp post.” It utilized very thin paper—the inmates had once found an entire roll of electrical insulation paper, which was perfect for the task—and the thinnest possible ballpoint pen. The letter was written in handwriting as fine as one could master and then rolled up tightly and wrapped in plastic harvested from a clear plastic bag. Tie it up tightly with thread, use a match to melt and seal the ends, and then add another layer of plastic—they called it a “shirt”—and another and so on for a total of five. Then swallow. Then wait for your conjugal visit. There was no telling exactly when the visit would occur—inmates knew when they were eligible for their biannual visit, but the exact timing was up to the administration. One might wait for a few days or a few weeks. One tried to eat as little as possible while waiting, to keep the number of bowel movements to a minimum. If it happened, though, one removed the outer “shirt” and swallowed the letter again. The conjugal visit, when it came, lasted three days. There would be plenty of eating then: Kovaliov’s wife would have carried bags of groceries on the train from Moscow and then the bus from Perm. At some point, she would swallow the letter, which she would smuggle out of the camp in her own intestines, undetectable to the guard who searched her in the gynecological chair on the way out, as she had on the way in. The third thing that Kovaliov learned from his conversation with the young captain was that this was why he was here, in cell confinement.

He had spent many nights in this building before, in short-term solitary confinement. For that, you were brought in wearing only your underthings and slippers. There was no mattress on the wooden bunk. What you did was put your slippers on the bunk in place of a pillow and go to sleep. An hour, maybe an hour and a half later you would be woken up by the shivering of your own body. You jumped up, did jumping jacks and squats, and when you were exhausted, you crouched with your back against the lone heating pipe in the cell—its tiny diameter ensured that the space could never be heated, and the pipe itself, most nights, was just barely warmer than your body. If you rubbed your back against it, though, after a while you were warm enough to return to the bunk. You placed your head on your slippers again and were out like a light. An hour later your own shivering body would awaken you again.

Regulations guaranteed inmates the right to document the temperature in their cell—by law it had to be no lower than 14 degrees Celcius (57 Fahrenheit) in solitary. The guards supplied a thermometer on demand. The thermometer in solitary always showed 14 Celcius, even when the corners of the cell sparkled incongruously white because the dampness had frozen solid.

Being cold was a definitive experience of the camp. It was winter when Kovaliov was first brought there, a particularly brutal one with temperatures of minus-40 (the point where Fahrenheit and Celcius meet) and below. His first dorm was Barracks Number One, where the walls were part wood and part rags, which inmates used to stuff in the gaps between logs. If you took a rag out—usually in order to try to stuff it back in more tightly—the gap that opened up, about two inches wide, provided a clear view of the camp grounds. The thermometer in the dorm truthfully reported the temperature as ranging between 6 and 7 Celcius (43–45 Fahrenheit). Kovaliov started noting down the temperature at fixed times twice a day.

“I see you are incorrigible,” a guard said when he noticed Kovaliov tracking the temperature. “You are continuing with your defamation.”

“Defamation of the Soviet authorities” was law-enforcement vernacular for the crime of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” for which Kovaliov had been sentenced.

“Whatever do you mean, sir?” Kovaliov responded. “Here is what the thermometer says, and here is what I wrote down—why would you call this defamation?”

Most of the time, though, in the dead of winter the guards stayed off the inmates’ backs. They turned a blind eye to the fact that the inmates wore their cotton-stuffed robes and felt boots to bed. Not that these kept them warm: it was impossible to be still and stay warm. When inmates were awake, they continuously moved around the dorm. They conducted all their conversations as they paced up and down the length and breadth of the barracks.

It wasn’t the guards’ humanity that surprised Kovaliov, though: Like many dissidents, he held to an abiding belief in the goodness of human nature. He had assumed that the guards in the camps were cogs in the repressive machine, men who could have been decent if their jobs were less punishing. It was their sadism that surprised Kovaliov—this was the second thing that working on Chronicles had not prepared him for.

“You’d be behind the barracks, gathering mushrooms or picking watercress and one of the guards would come over and start humiliating you,” Kovaliov told me. “He wouldn’t reprimand you, he would just take pleasure in telling you, say, that you were turning into a sheep.”

Kovaliov was talking to me in his Moscow apartment. After he was released from the camps in 1982, he spent three years in internal exile in the Kolyma Region in the Far East. He returned to Moscow in time for perestroika and became a public political activist. In 1994 President Yeltsin appointed him his human rights ombudsman, a job Kovaliov soon lost for his harsh criticism of the war in Chechnya. He served three terms in the Russian parliament before becoming, under Putin, once again a dissident. It was as a dissident that he attended all of Shmyrov’s Sawmill festivals.

So how did it feel to be transported back into the space where his body and his spirit had suffered such abuse?

“Wonderful!” he exclaimed.

He saw my incredulous expression and explained: “You were just there at the wrong time of year.”

I had visited Perm-36 in April, when the snow had melted into large, deep puddles that stood perfectly still, the same dense shade of gray as the low sky.

“You should see it in the summer. Some evenings there—the light is special, and the air—sometimes you’d be going behind the outhouse, because inside it was rather unpleasant and inconvenient and you avoided it if you could, so there you’d be, taking a piss behind the outhouse, and the air was like you could touch it, and the smell of those linden trees, and the sound of the birds singing.”