The Coalition’s Global Initiative for Justice, Truth and Reconciliation has been working with civil society organizations in Sri Lanka since 2015 to facilitate communication between local communities and the government of Sri Lanka as it undertakes on its transitional justice process. As part of this effort, Dina Bailey, the Coalition’s Director of Methodology and Practice, recently traveled to the country to facilitate youth-focused dialogue programs. Here, she shares her reflections on the experience and her hopes for the future.

Maya Angelou once said, “Perhaps travel cannot prevent bigotry, but by demonstrating that all peoples cry, laugh, eat, worry, and die, it can introduce the idea that if we try and understand each other, we may even become friends.” In all of my travels, I have found this quote to be true; and, facilitating a training in Sri Lanka over the summer brought Angelou’s convictions home once again. Over approximately fifteen days, my Coalition colleague, Devon Gulbrandsen — Compliance and Program Liaison for the Coalition’s Global Initiative for Justice, Truth and Reconciliation — and I worked with local partner organizations from South Africa and Sri Lanka to bring together young Sri Lankans in three different, and often contentious, regions of the country. Many of the youth were just small children during the country’s civil war between the Sri Lankan government and the island’s Tamil minority (1983-2009) and still struggle to process the brutal conflict.

As I was given opportunities to learn more about the people of Sri Lanka, the country’s historical (and present) conflict, and the legacies that persist, I was tasked with sharing my knowledge of dialogue — the ways in which people may come together to share ideas, information, experiences, and  assumptions for the purposes of personal and collective learning — and how dialogue may be used to bring people a little closer together. I am well used to traveling to different parts of the world and exploring a place’s complexity. In bearing witness to a country’s victories and struggles, I have the opportunity to see more depth and authentic beauty; even over relatively short trips, I also find that I come to understand myself and others better.

assumptions for the purposes of personal and collective learning — and how dialogue may be used to bring people a little closer together. I am well used to traveling to different parts of the world and exploring a place’s complexity. In bearing witness to a country’s victories and struggles, I have the opportunity to see more depth and authentic beauty; even over relatively short trips, I also find that I come to understand myself and others better.

While we were in Sri Lanka, our local partners brought together cohorts of young adults from various ethnic backgrounds — generally, participants identified as Sinhalese, the majority in Sri Lanka; or Tamil, the minority. In Galle, the participants were mainly Sinhalese; in Batticaloa, the participants were Tamil and Sinhalese; and, in Jaffna, the participants were mainly Tamil. Each cohort brought its own perspective of the country’s past violence, the country’s current conflicts, and how much faith they had in moving the country forward into a more peaceful and inclusive future.

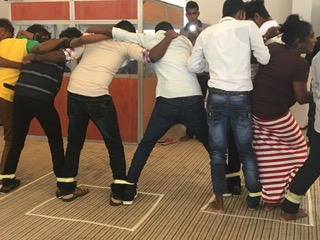

Following a day-long training by our South African partners on truth and reconciliation commissions and transitional justice — from both global and national perspectives — I began the dialogue training which focused on: recognizing multiple truths, asking more effective questions of ourselves and others, building dialogic programs through the Arc of Dialogue methodology, and preparing for interpersonal conflict and challenges when people come together to talk about topics about which they feel passionate. Over the last portion of our four-day training cycle, the Sri Lankan partners guided participants through the development of action plans with the hope that they would return to their communities and use their knowledge of truth, reconciliation and dialogue to lead a program or a series of programs related to topics that align with the main tenets of transitional justice.

Dialogue asks its facilitators and participants to realign how they measure success — success is not based on  how many people attend a particular program or on whether all of the content on a pre-determined agenda has been covered. Rather, a successful dialogue means that each person focuses on learning about themselves and others. During a dialogue, personal truths are shared; participants recognize similarities and differences in their personal experiences; participants talk about how societal assumptions, roles, and policies shape collective responsibilities; and, finally, participants reflect on what they have learned during the dialogue and how they will use that new knowledge in future decisions and actions. In Sri Lanka, the participants learned not only how to engage in productive dialogue themselves, but how to successfully facilitate dialogic programs. The best facilitators are those who:

how many people attend a particular program or on whether all of the content on a pre-determined agenda has been covered. Rather, a successful dialogue means that each person focuses on learning about themselves and others. During a dialogue, personal truths are shared; participants recognize similarities and differences in their personal experiences; participants talk about how societal assumptions, roles, and policies shape collective responsibilities; and, finally, participants reflect on what they have learned during the dialogue and how they will use that new knowledge in future decisions and actions. In Sri Lanka, the participants learned not only how to engage in productive dialogue themselves, but how to successfully facilitate dialogic programs. The best facilitators are those who:

- give equal value to emotional, intellectual and spiritual ways of knowing

- exhibit a natural “spirit of inquiry” or curiosity

- listen intently while reserving judgment

- are aware of and reflective about their own identities

- have organized, but flexible ways of working and thinking

- show patience with diverse learning processes and diverse learners

- hold themselves and others accountable for behaviors and attitudes

Throughout each four-day training in Sri Lanka, the cohort participants grew closer. They did so to varying degrees and in different ways. The moment that stands out most for me happened in Batticaloa. We had three different languages being spoken — English, Tamil and Sinhala — with people coming from various lived experiences and cultural backgrounds. As rapidly as multiple language translations were happening, cultural translations were happening just as fast. The students were expected to bring to light their personal viewpoints while recognizing the validity of others’ viewpoints. While questions were asked and answered, activities were completed, and challenging topics were broached, the students initially took comfort in the familiar — sitting next to those who were of the same cultural group, working in those same cultural groups during breakouts (partially due to difficulties in translating across languages during small group discussions), and having fun within their cultural groups during free times. One day, I went out during the coffee break. I noticed a

Throughout each four-day training in Sri Lanka, the cohort participants grew closer. They did so to varying degrees and in different ways. The moment that stands out most for me happened in Batticaloa. We had three different languages being spoken — English, Tamil and Sinhala — with people coming from various lived experiences and cultural backgrounds. As rapidly as multiple language translations were happening, cultural translations were happening just as fast. The students were expected to bring to light their personal viewpoints while recognizing the validity of others’ viewpoints. While questions were asked and answered, activities were completed, and challenging topics were broached, the students initially took comfort in the familiar — sitting next to those who were of the same cultural group, working in those same cultural groups during breakouts (partially due to difficulties in translating across languages during small group discussions), and having fun within their cultural groups during free times. One day, I went out during the coffee break. I noticed a  large group laughing together. Curious, I drew closer. Two of the young men (one Tamil and the other Sinhalese) were teasing each other in English. To me, witnessing the moment when the Tamil and Sinhalese youth voluntarily bridged the language barrier and were comfortable enough to tease each other gave me hope for humanity.

large group laughing together. Curious, I drew closer. Two of the young men (one Tamil and the other Sinhalese) were teasing each other in English. To me, witnessing the moment when the Tamil and Sinhalese youth voluntarily bridged the language barrier and were comfortable enough to tease each other gave me hope for humanity.

I do not mean to exaggerate the effects of dialogue training nor am I claiming that those participants may no longer make assumptions or take part in conflicts that have claimed generations of Sri Lankans. However, as with Angelou’s quote, I find hope in that a number of youth in Sri Lanka could come together to laugh, talk, listen and take action; they came together and found friends in a perhaps unexpected place.