“I think we were not conscious of the mistreatment we suffered as women, at least not as conscious as we are today. In that situation, we did not talk about it or we were ashamed to speak about it.” – Testimony of a former female detainee at ESMA

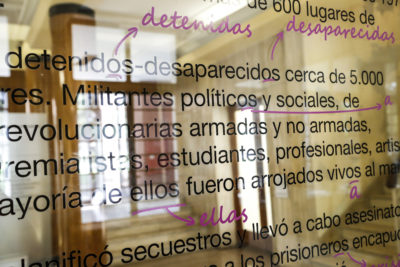

During the Argentine civic-military dictatorship of 1976-1983, a widespread system of economic, political and social persecution took hold of the country – supported by over 600 illegal detention centers, where social activists and political prisoners were detained, tortured and disappeared. Some 30,000 are still missing.

During the Argentine civic-military dictatorship of 1976-1983, a widespread system of economic, political and social persecution took hold of the country – supported by over 600 illegal detention centers, where social activists and political prisoners were detained, tortured and disappeared. Some 30,000 are still missing.

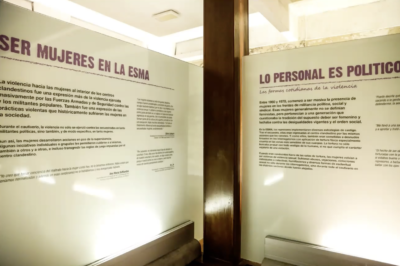

Women were detained and tortured alongside men, yet their particular experiences have been less explored. To begin to rectify this situation, the Coalition awarded a 2018 Project Support Fund grant to Coalition member Museo Sitio de Memoria ESMA – the site of Argentina’s largest former clandestine torture center, where nearly 5000 people died – to develop and share an exhibit entitled Being Women at ESMA – Revisiting Testimonies (Ser mujeres ESMA – testimonios para volver a mirar). The exhibit opened on March 14, 2019.

“ESMA’s permanent exhibition does not focus on the gender or sexual violence exerted on women during their captivity,” explains María José Kahn, a Curator and Program Director at ESMA. “We noticed this omission soon  after the museum opened in 2015. Particularly in light of recent feminist social movements, we knew we needed to look back to the testimonies women gave during the trials and correct this mistake.”

after the museum opened in 2015. Particularly in light of recent feminist social movements, we knew we needed to look back to the testimonies women gave during the trials and correct this mistake.”

Kahn explains that when the country’s truth and reconciliation tribunals first began in the 1980s, testimonies focused largely on proving that the secret detention centers existed at all and that disappearances were an actual issue, but as the decades have unfolded – aided by women’s activism, and women’s own changing perception of themselves – women’s particular stories have come to the forefront.

“The exhibition seeks to create a space for audiences to be able to take a deeper look at the testimonies given about women’s incarceration conditions,” says Kahn.

The new exhibit is intertwined into the permanent one and was based on testimonies given by formerly detained women. What surfaces is a portrait of women’s experiences of captivity – one that included sexual humiliation, brute intimidation and extreme cruelty. More than 500 babies were born to detained women and then stolen by the military.

“Many women [gave birth] to children blindfolded…prevented from seeing their children,” explains one of the testimonies captured on an exhibit panel.

Women were also subjected to other forms of emotional and psychological torture unique to their gender.

“At three in the morning, the guards woke us up and saying, ‘Let’s see you subversives get up and dress as women. Put on make-up, get ready to go out.’ You didn’t know if you were going on a death flight – to be dropped out of an airplane – if you were going to be shot in a plaza, abandoned in a vacant lot, or something else. That night, we ended up in ‘El Globo,’ a restaurant, where we forced to have dinner with our perpetrators,” says one panel testimony.

“At three in the morning, the guards woke us up and saying, ‘Let’s see you subversives get up and dress as women. Put on make-up, get ready to go out.’ You didn’t know if you were going on a death flight – to be dropped out of an airplane – if you were going to be shot in a plaza, abandoned in a vacant lot, or something else. That night, we ended up in ‘El Globo,’ a restaurant, where we forced to have dinner with our perpetrators,” says one panel testimony.

“For perpetrators,” says Kahn “these women were seen as subversives because of their double condition: first because of their social and political activism, but also because of the way in which their lifestyles broke with the established gender values.”

The exhibition will remain at ESMA for three months and will then travel to other institutions, including universities, schools and civil society organizations and will be complemented with public programming.

“We want this exhibition to open new ways for audiences to reflect on the experience of being a woman in both the past and the present,” says Kahn. “We hope that our audiences are able to identify the different forms of violence women have experienced, and still experience today, and also learn how, over time, we have been  able to better listen and understand these testimonies. And we hope by doing so, visitors may reflect on their own actions in order to build a better society.”

able to better listen and understand these testimonies. And we hope by doing so, visitors may reflect on their own actions in order to build a better society.”