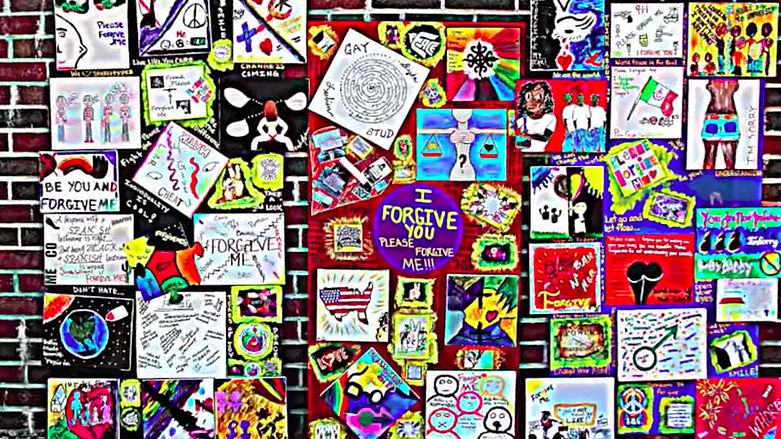

The Justice Fleet is a mobile Site of Conscience based in St. Louis, USA, that fosters community healing around racism and identity through art, play, and dialogue. Housed inside of box trucks, the Justice Fleet currently consists of four mobile exhibits – Radical Imagination, Radical Forgiveness, Transfuturism and Black Girl Magic – that are all designed to engage community members in discussions about implicit and explicit bias, social justice, and empathy. The goal is to activate communities in imagining and building a world without injustice. In the aftermath of the violence at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, the Coalition talked with the Justice Fleet’s Founder, Amber Johnson, about the emotional toll racism takes on all people, the role of Sites of Conscience in healing marginalized communities, and the steps involved in radically reimagining our world.

In your work at the Justice Fleet, you have talked about the “invisible labor” you have undergone in your own life as – to borrow your words – “a black, queer, gender non-conforming, sometimes femme, sometimes not, human.” You seem to be referencing the internal, emotional struggle of being a person in a world that is handcuffed by injustice and oppression. Can you speak a bit more about that?

Invisible labor is about the mental, emotional and physical work that someone has to do just to survive and exist; it’s the stuff that you don’t see. One “everyday” example would be combing hair. As a Black person my hair regimen is very different from the average American’s. I have to find hair care products that are specifically for my hair type, and it requires a lot of labor to make it presentable – labor that isn’t typical for or even known to the “average,” white American.

Another example is going to the doctor’s office – because of medical racism there is a lot of fear. I have a lot of trauma around doctors – not being listened to, being completely dismissed, not being treated for things. When it’s time for me to go to the doctor, there is a certain amount of energy I have to exert just to show up. In addition, as a teacher, I am one of two Black people in my department, the only non-binary person, and one of two queer people. That means that all students who have issues around intersectional power and identity come to me, so that is another form of invisible labor. None of my other colleagues see that, but I am constantly mentoring these students – students of color, non-binary and trans students – because they see me as safe, where no one else is. It’s these “little” things – the emotional, physical and mental labors that marginalized people have to do because of who we are that other people do not have to do.

While there is no doubt people of color feel this strain or “invisible labor” most acutely, the stress of racial injustice hurts all Americans. I am reminded of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s comments at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 when he spoke directly to white Americans who were distressed to “see the old ways crumbling,” saying: “When it has [crumbled], you will find that a burden has been lifted from your shoulders, too. It is not just a question of guilt, although there is that. It is that men cannot live with a lie and not be stained by it.” From your work with local communities, can you say a bit about the psychological impact of centuries of systemic racism on the country as a whole?

The psychological impact of racism is long. One simple way to think about it is to consider how stress impacts the body and what type of situations cause stress. Think about the “Karen” phenomenon – Karen being a derogative term used primarily in the United States for white women who use their privilege against people of color. If a white woman is in a space and feels the need to attack a Black person because she thinks they are not up to code or that they stole her phone or they parked in her spot – whatever it is – that person, that Karen, who is getting worked up and calling the police, is creating stress for themselves. The person who is routinely disgusted by how someone else looks, that disgust causes stress for them. In this way, oppression, psychologically, psychologically, affects everyone. Obviously it affects everyone differently, and some more than others. For example, once a Karen leaves that stressful situation, their stressors are likely taken down a notch. The victims of her rage, however, are likely to have their stress remain constant or increase for quite some time. Maybe it ruins their day or week, or maybe the routine nature of these attacks puts them in a constant state of being “on guard.” It’s important to think about this on a more structure level too – for instance, the American prison system. The guard who works in a prison is in the prison almost as many hours a day as a person who is incarcerated. There is a stress there. These systems impact everyone who is a part of them, not just those who don’t have power.

The psychological impact of racism is long. One simple way to think about it is to consider how stress impacts the body and what type of situations cause stress. Think about the “Karen” phenomenon – Karen being a derogative term used primarily in the United States for white women who use their privilege against people of color. If a white woman is in a space and feels the need to attack a Black person because she thinks they are not up to code or that they stole her phone or they parked in her spot – whatever it is – that person, that Karen, who is getting worked up and calling the police, is creating stress for themselves. The person who is routinely disgusted by how someone else looks, that disgust causes stress for them. In this way, oppression, psychologically, psychologically, affects everyone. Obviously it affects everyone differently, and some more than others. For example, once a Karen leaves that stressful situation, their stressors are likely taken down a notch. The victims of her rage, however, are likely to have their stress remain constant or increase for quite some time. Maybe it ruins their day or week, or maybe the routine nature of these attacks puts them in a constant state of being “on guard.” It’s important to think about this on a more structure level too – for instance, the American prison system. The guard who works in a prison is in the prison almost as many hours a day as a person who is incarcerated. There is a stress there. These systems impact everyone who is a part of them, not just those who don’t have power.

At this pivotal moment, there is a lot of language around racial unity and many have spoken out in favor of a variety of processes that can help America both make a symbolic break with its past and adopt concrete policies that will help survivors heal and ensure a more equitable and inclusive future — truth commissions, reparations, accountability measures, etc. How can we ensure that everyday people are engaged in these processes and benefit from them? How can memorialization initiatives like the Justice Fleet support or play a direct role in these processes?

I think there is a misnomer in the rhetoric around racial unity and the call for healing. Sometimes, the call for racial unity and healing presupposes that all parties are at fault. But I am not at fault, and I don’t need to automatically unify with my oppressor. Instead, I need my oppressor to stop oppressing me so that we can both grow together.

I think there is a misnomer in the rhetoric around racial unity and the call for healing. Sometimes, the call for racial unity and healing presupposes that all parties are at fault. But I am not at fault, and I don’t need to automatically unify with my oppressor. Instead, I need my oppressor to stop oppressing me so that we can both grow together.

When I think about the Justice Fleet’s role in that, our role is giving people the tools to start healing because healing must come before any attempts to unify. At the Justice Fleet, we support something called “healing justice,” which is the idea that we have to heal from our traumas in order to move forward. “Humanized equity” is our approach to this – it basically says that those that are the most impacted by injustice need to be the face of the solution, need to be the ones who are building up solutions and dreaming up new worlds – because they have a much fuller, holistic and nuanced understanding of what is going on. At the Justice Fleet, we support projects that provide spaces for marginalized communities, and those who care about them, to do just this. They are, after all, the ones who know best the trauma, pain and discomfort that comes from systemic racism. In other words, we need spaces for this healing to happen and plans of action before unity can happen – and that’s an important role for Sites of Conscience to play in any local or national truth and justice processes that might take place in America. I believe abusive systems and people can be mended and that unity can ultimately occur, but I think a lot of sharing, listening and healing needs to happen first.

If we think about the 2020 protests for racial equity, the new Biden-Harris administration, and the most recent spike of white supremacy in America, which culminated in the violence at the Capitol on January 6th, America is clearly all over the place on race, making the idea of “racial unity” even in the future appealing, but also daunting. In your work at the Justice Fleet, you talk a lot about “radical imagination.” Can you say a bit more about what that is and how it might be useful in today’s world?

Radical imagination is absolutely pivotal; it’s so important right now. We’ve seen with the COVID-19 pandemic that everybody is suffering, and that our social and economic systems in America so often benefit those at the very top. During the pandemic, billionaires saw a rapid increase in their income and their net worth, while millions of average Americans lost their jobs. Capitalism doesn’t help anybody. And COVID-19 has also highlighted how disparities in health care have disproportionately hurt people of color in this country.

So how do we move forward? We cannot go back to the “normal,” and nor can we treat this “new normal” as ok. Instead, we have to radically reimagine ways to be in the world. We have to reimagine what the work week looks like, we have to reimagine what education looks like. Virtual school has actually been a blessing for some children – children who deal with bullying, children who deal with social anxiety. But it has also been a curse for other children – children who are extroverts, children who have particular kinds of learning disabilities that require more tactile and personalized learning strategies. In this case, COVID-19 has shown us that there are accommodations that can happen; we have just chosen not to use them.

Radical imagination is all about reimagining brave, new ways to be in the world. We complain about the conditions of this society, not realizing that almost all those complaints are rooted in capitalism and other systems that are inherently racist. One challenge for Sites of Conscience is to help shine a spotlight on inequities all of us live with every single day. We don’t think about the air we breathe, until it is taken from us. COVID-19 has taken a lot of things from us and now we see that things have to change. So, in many ways, we have been given an opportunity here – to radicalize, to say, hey, we can’t do the things we used to and we can’t do things the way we are doing them. What’s next? Most people are so constrained by what has happened and what is happening that it is really hard to see what’s next. So that’s what radical imagination does, it pushes us to think about what is next, beyond the constraints of what is now.