While same-sex conduct is not technically criminalized in the Dominican Republic, unlike many Caribbean countries, LGBTQI+ Dominicans routinely face violence and discrimination. In this interview, the Coalition speaks with Laura Pérez, Deputy Director of the Memorial Museum of the Dominican Resistance (MMRD), a Site of Conscience in Santo Domingo, about their recent Project Support Fund which allowed them to research and connect the experiences of LGBTQI+ communities under the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) with their contemporaries today. A link to their completed toolkit in Spanish is available here.

Dictator Rafael Trujillo ruled the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his assassination in 1961. During this time, numerous human rights atrocities took place, including the infamous Parsley massacre in 1937, which claimed the lives of an estimated 20,000 Haitians. For those unfamiliar with this context, can you say a bit more about Trujillo’s dictatorship and its legacy?

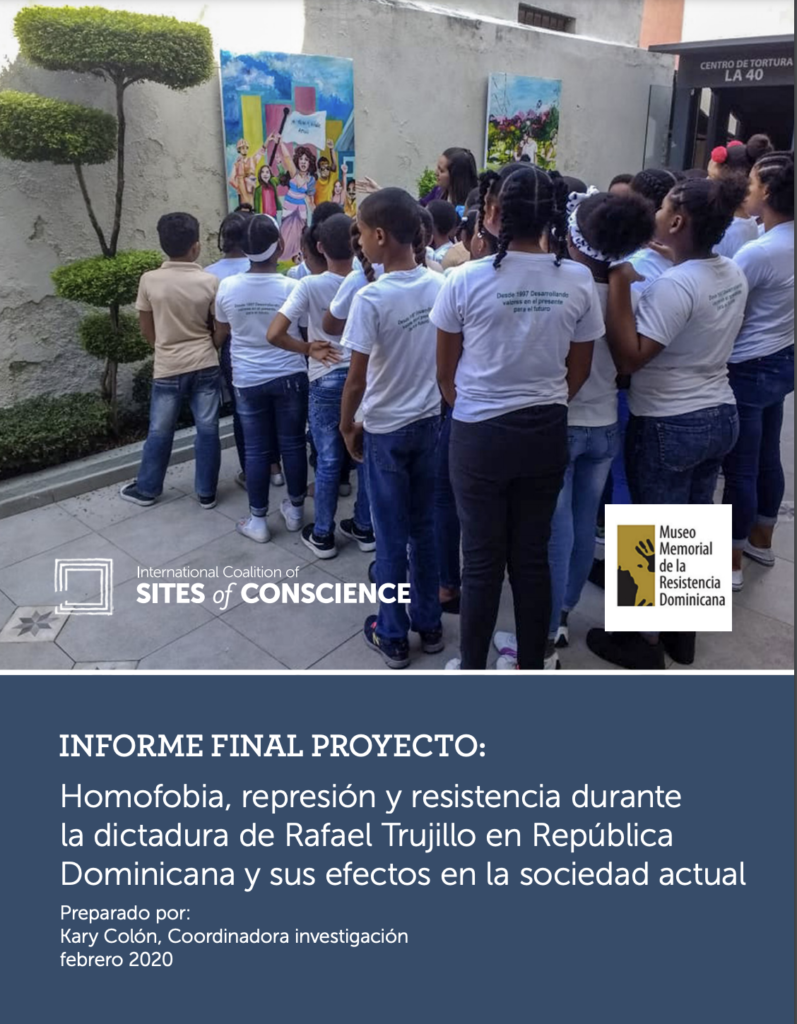

Our museum’s mission is to educate our visitors about human rights and democratic principles by using the experiences of the past to help increase civic awareness about our history and build a better future. During the Rafael L. Trujillo dictatorship, which lasted over thirty years, there were many serious human rights violations and crimes against humanity committed that were never acknowledged, much less put through a transitional justice process. Because of this approach, this lack of justice, our democracy is not entirely built on a strong foundation. It has turned a blind eye to impunity and consequently many of the actors during the dictatorship, or their successors, remain in government today.

One of the biggest legacies of this lack of justice is that today in the Dominican Republic minorities still face systemic discrimination, particularly the LGBTQI+ community, migrants, women and the poor. Our police forces, who are supposed to protect the people, continue to repress these groups in ways very reminiscent of the dictatorship.

In 2019, the Memorial Museum of the Dominican Resistance received a Project Support Fund grant to research and share the experiences of LGBTQI+ communities under the dictatorship. Can you tell us about your findings and what they add to our understanding of this period?

Through our research, we found that the LGBTQI+ community under Trujillo was routinely debased and used as a political weapon by the dictatorship. Knowing that calling someone gay would tarnish them in a way that could literally destroy their lives, the dictatorship would “accuse” political opponents of being homosexual (although in most cases, they were not). For example, to mark opponents or even supporters who had fallen out of favor, they would accuse these people of being gay, which, in turn, made them – as well as their families and loved ones – effectively pariahs. People would lose their jobs, get thrown out of their houses, and even get killed. The dictatorship would encourage this reaction by the public and government officials by using official propaganda to cast homosexuality as a social evil, and homosexuals as criminals and “enemies of the government.” Homosexuality was even used to justify murders or to cover them up.

As this relates to today, our research revealed how the real faces and fates of the LGBTQI+ community were never prioritized or accepted. Their stories and concerns were completely overshadowed by this systemic discrimination; they were void, invisible, they didn’t exist. We were not expecting the severity of impact that this would have, but it truthfully perfectly explains the negative connotation that LGBTQI+ terms have today and the systemic violation of rights still suffered by the LGBTQI+ community. Today, state forces are constantly persecuting LGTBQI+ persons. For example, near our museum in the Colonial City is a park where LGTBQI+ people gather to hang out, but they are routinely harassed by neighbors, passer byers, and both the Tourist Police and the National Police.

Can you speak a bit about your methodology? Did you speak with survivors of the regime? How have their lives changed because of these experiences?

We used a mixed methodology of data recollection with interviews, focal groups, old testimonies, and documents, etc. We chose a mixed methodology because we were investigating incidents and actions that occurred between 60 to 90 years ago. Our team included an anthropologist, historian, lawyer, sociologist and an LGTBQI+ studies specialist. It was hard to do this investigation because many of the persons involved had passed away or were too old and didn’t want to talk about those difficult memories.

What connections can you make between the discrimination LGBTQI+ communities under Trujillo faced and the current climate for LGBTQI+ rights in the country?

The connection was the most important finding. Analyzing just how closely the dictatorship equated masculinity,legitimacy and power really helped explained the roots of the modern collective Dominican mindset, which prioritizes the “manly man.” Young boys and men are encouraged to aspire to this ridiculous ideal, and as a result, the LGBTQI+ community has come to be seen as the opposite of this ideal – as something negative, something that all are encouraged to bully, make fun of, reject and even “correct.” Few worry about denying the LGBTQI+ community their rights because they are so ostracized publicly. This line of investigation must continue because it will give deeper meaning to so much of the violence we see against this community today.

What projects and programming is MMRD conducting to raise awareness of this history and its impact on today?

Our Project Support Fund grant has helped us grow our programming and partnerships. For instance, it enabled us to collaborate with the United Nations Development Program’s project “Being LGBTI in the Caribbean” on an exhibition that will showcase our findings with the artistic work of the LGBT community. Due to the pandemic we haven’t set a date, but we expect to open it this year. Like most of our exhibitions we plan to take it outside Santo Domingo, the main city, with our program “El Museo Visita” (The Museum Visits), which brings our temporary exhibitions, and some elements of our permanent exhibition, to towns outside Santo Domingo.