This blog – by Samantha Hunter, a Specialist in Education at Eastern State Penitentiary – is the first in a series of posts from participants in our groundbreaking three-year initiative From Brown v. Board to Ferguson: Fostering Dialogue on Education, Incarceration and Civil Rights.

Putting together a youth program for the From Brown v. Board to Ferguson program was a new and daunting challenge for us at Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. As a staff, we struggled with the idea of talking about issues of race, education inequality and incarceration with young people. Would they understand the issues? How would we keep them engaged? Where did we begin? We grappled with these questions until our first program with the Teva Pharmaceutical Interns from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Only then did we realize that young people are as committed to exploring and learning about these topics as we were. More than that: They were already talking about them.

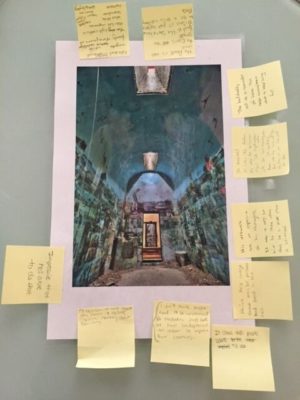

Built in 1829, Eastern State Penitentiary was once the most famous and expensive prison in the  world. Known for its grand architecture and strict discipline, it was the world’s first true “penitentiary,” a prison designed to inspire penitence, or true regret, in the hearts of prisoners. Today it is essentially a ruin – a haunting world of crumbling cellblocks and empty guard towers. In this regard, it was the perfect backdrop to host a discussion about the inequities in incarceration today.

world. Known for its grand architecture and strict discipline, it was the world’s first true “penitentiary,” a prison designed to inspire penitence, or true regret, in the hearts of prisoners. Today it is essentially a ruin – a haunting world of crumbling cellblocks and empty guard towers. In this regard, it was the perfect backdrop to host a discussion about the inequities in incarceration today.

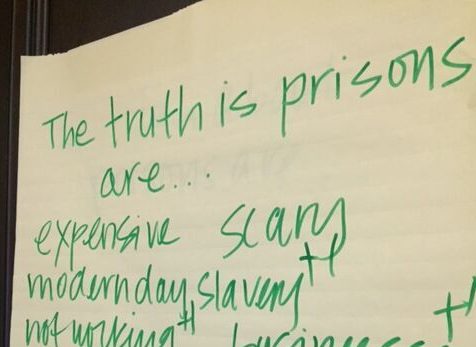

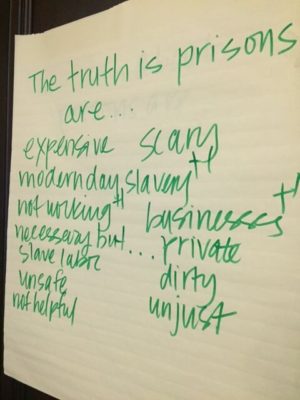

This was clear from our first dialogue session, which took place after students toured the site. For this, we sat them in a circle and gave them one task – to finish the sentence: “The truth is prisons are…” with just one word or phrase. Their responses – “modern day slavery,” “slave labor,” “unjust and unnecessary, but…” revealed that they had not only thought about these issues, but that they felt them.

From this simple exercise, we moved straight into contemporary topics surrounding incarceration, including voter disenfranchisement, the school-to-prison pipeline and mandatory minimum sentencing. This last one was particularly unsettling to them. You could see them struggling to come to terms with the facts before them, which the Sentencing Project sums up well:

From this simple exercise, we moved straight into contemporary topics surrounding incarceration, including voter disenfranchisement, the school-to-prison pipeline and mandatory minimum sentencing. This last one was particularly unsettling to them. You could see them struggling to come to terms with the facts before them, which the Sentencing Project sums up well:

“Today, people of color make up 37% of the U.S. population but 67% of the prison population. Overall, African Americans are more likely than white Americans to be arrested; once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to face stiff sentences. Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men and Hispanic men are more than twice as likely to be incarcerated as non-Hispanic white men.”

The fact that people of color were targets of unjust laws were themes that the students referenced throughout the rest of the session. One student made the comparison between the lack of accountability for those responsible for the mortgage bubble and financial crisis of the early 2000s versus the number of Black musicians incarcerated today for possessing marijuana.

After unearthing these issues, we transitioned into an art response activity by asking the students to react to two pieces by Philadelphia artists related to incarceration: Jesse Krimes’ Apokaluptein16389067:11 and Mark Strandquist’s Windows from Prison. The students were separated into two groups, given one of the two artworks and a notecard, and asked to respond to the image individually and with their small group. After the groups had time to discuss the image, they switched art pieces and repeated the process. We then discussed both images as a group.

As facilitators, this was a highlight. We felt our voices drift away and watched the students take over, leading the discussion and going places we did not necessarily expect. On Apokaluptein16389067:11, they were favorable – some compared the art to the taste of freedom, the feeling of flying, and being hopeful. Both groups were far more critical of Windows from Prison. A few students said the series, available here, represented a fundamental misunderstanding between people who are incarcerated and people who are not. While the photographs were meant to be motivational, the students thought they could ultimately be damaging, hurtful – reminding those incarcerated of a life they were missing out on or might not see again for decades. We realized then that inspiring empathy was one of the greatest outcomes of dialogue.

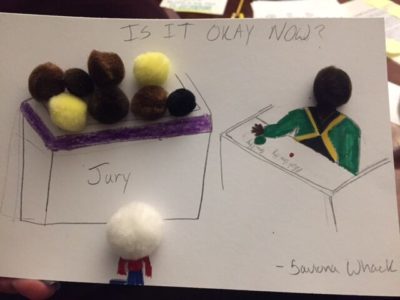

Finally, to give the students a space to organize, process and synthesize what we discussed throughout the entire session, the session concluded with the students creating their own artwork based on the prompt: “Imagine you are in Philadelphia Mayor Kenney’s office and are about to advocate for prison reform. Create an art piece – a poem, slogan, or drawing – to get your message across to the mayor. In your art, include the issues you are most passionate about. It could be one we discussed today (i.e. mass incarceration, school-to-prison pipeline, or mandatory minimums).”

A few students shared their art with the group: one wrote a poem to Mayor Kenney on the School-to-Prison Pipeline, another drew a picture of the United States on trial for the harsh and unjust treatment of people of color. Every student had something to say and was grateful for a space to say it. One student wrote that he learned more about these issues during our session than he did in school. I realized, then, it did not matter that our program was not perfect – that we did not have all right questions; that we did not have everything figured out ahead of time. What mattered was that we created this space for students to feel comfortable enough to have these conversations with us, each other and themselves.

A few students shared their art with the group: one wrote a poem to Mayor Kenney on the School-to-Prison Pipeline, another drew a picture of the United States on trial for the harsh and unjust treatment of people of color. Every student had something to say and was grateful for a space to say it. One student wrote that he learned more about these issues during our session than he did in school. I realized, then, it did not matter that our program was not perfect – that we did not have all right questions; that we did not have everything figured out ahead of time. What mattered was that we created this space for students to feel comfortable enough to have these conversations with us, each other and themselves.

Photos courtesy of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.