While leaders around the globe cast doubt on climate change, the effects of global warming and rising sea levels are taking an increasingly human face. From the outskirts of Santiago, Chile – where farmers must contend with the effects of urbanization – a struggle Coalition member Memorial Paine documents and resists – to Japan, where another member, CORE, works to raise awareness of the consequences of radiation exposure, the human stories show us that environmental issues are directly tied to human rights.

Africa has been disproportionately affected by climate change. Although the continent produces only a small amount of the world’s greenhouse gasses, according to a 2014 report by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Africa’s land temperature is likely to rise faster than the global land average, with extensive areas of Africa exceeding a 2°C rise by the last two decades of this century relative to the late 20th century mean annual temperature. The effects of this trend on Africans are already evident, with millions throughout the continent malnourished and displaced by droughts and flooding.

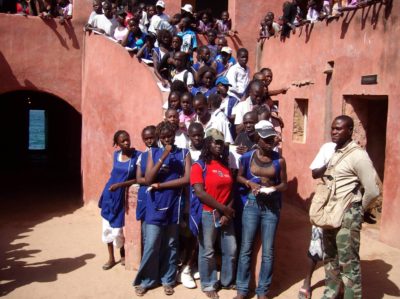

Africa also offers evidence of the consequences climate change has on historic sites and the people they serve. Founding Coalition member Maison des Esclaves, located on Gorée Island in Senegal – the first UNESCO World Heritage site in Africa – is one testament to this.

Built around 1776, Maison des Esclaves is a striking red house that overlooks the port of Dakar on the Atlantic Ocean and shares the history and narratives of the vast transatlantic slave trade. Since established as a museum in 1962, it has told personal stories of a private home and the role of its owners in both local business and the slave trade. It is currently undergoing a major revitalization – overseen by the Coalition with the support of the Senegalese Government and the Ford Foundation – that will ensure its potential to serve as a repository of knowledge and a catalyst for dialogue on contemporary forms of slavery. Its signature feature, the “Door of No Return,” which leads from the house directly to the Atlantic Ocean, stands as a powerful symbol of the brutality and pervasiveness of the slave trade past and present.

Built around 1776, Maison des Esclaves is a striking red house that overlooks the port of Dakar on the Atlantic Ocean and shares the history and narratives of the vast transatlantic slave trade. Since established as a museum in 1962, it has told personal stories of a private home and the role of its owners in both local business and the slave trade. It is currently undergoing a major revitalization – overseen by the Coalition with the support of the Senegalese Government and the Ford Foundation – that will ensure its potential to serve as a repository of knowledge and a catalyst for dialogue on contemporary forms of slavery. Its signature feature, the “Door of No Return,” which leads from the house directly to the Atlantic Ocean, stands as a powerful symbol of the brutality and pervasiveness of the slave trade past and present.

Yet coastal erosion on Gorée Island is a persistent threat to the site’s physical structure and livelihood. In particular, rising sea levels are escalating the deterioration of the seawall around parts of the island, putting Maison des Esclaves at grave risk – as are other historic sites along the water, including a mosque on the  island’s west coast which Augustin Senghor, the mayor of Gorée Island, recently told Seneweb could find itself “at the bottom of the sea.”

island’s west coast which Augustin Senghor, the mayor of Gorée Island, recently told Seneweb could find itself “at the bottom of the sea.”

The situation puts at risk not only physical structures and residents of the island, but the island’s economy, which is heavily dependent on tourism. “Increasingly areas are closed for visitors as they become dangerous and there is not [a sufficient] budget to repair and rehabilitate them,” explained Guiomar Alonso Cano, Regional Advisor for Culture at UNESCO’s regional office in Dakar, in a recent interview with the Coalition.

The situation on Gorée Island presents a serious challenge to historic preservationists – one that is increasingly shared with their colleagues around the world. In the United States, because of rising sea levels and acidic soil, archeologists working at Jamestown in Virginia – the first permanent English settlement in the Americas – are rushing to uncover sections of Jamestown Island, a site adjacent to the historic town, that are still buried. “As we are looking forward to [mid-century], there will be significant areas of Jamestown Island under water,” historian Dr. James Horn told The Guardian in 2015. “There’s always a race against time, but there’s a greater urgency in the case of Jamestown because of climate change.”

What is at stake is history itself, and the tangible, irreplaceable experiences that Sites of Conscience offer visitors. As Eloi Coly, the Site Manager and Curator of Maison des Esclaves, told the Coalition, “Increasingly severe storms, a result of climate change, could, if unchecked, threaten the physical existence of Maison des Esclaves.”

Coly noted that the revitalization effort currently underway at Maison des Esclaves will approach the effects of climate change on the site in an integrated and robust manner. As for Gorée Island more generally, preservationists are advocating for stronger protective walls around the island and long-term strategies to halt erosion. “Gorée Island celebrates the 40th anniversary [of its UNESCO World Heritage standing] in 2018,” Alonso said. “Together with national authorities, UNESCO is planning to launch a major international campaign to 1) fight coastal erosion in the area and 2) rehabilitate emblematic buildings on the property which are seriously deteriorated…The challenge is important and systematic solutions need to be found.”

Coly noted that the revitalization effort currently underway at Maison des Esclaves will approach the effects of climate change on the site in an integrated and robust manner. As for Gorée Island more generally, preservationists are advocating for stronger protective walls around the island and long-term strategies to halt erosion. “Gorée Island celebrates the 40th anniversary [of its UNESCO World Heritage standing] in 2018,” Alonso said. “Together with national authorities, UNESCO is planning to launch a major international campaign to 1) fight coastal erosion in the area and 2) rehabilitate emblematic buildings on the property which are seriously deteriorated…The challenge is important and systematic solutions need to be found.”