Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte, North Carolina (USA) is an interactive history museum that provides the nation with the most comprehensive interpretation of post-Civil War southern society. In this essay, former Vice President of Exhibitions Kate Baillon and former Vice President of Education Kamile Bostick discuss the museum’s rapid response efforts after an officer-involved incident that took the life of a local African American man in 2016 caused widespread protests throughout Charlotte.

On September 20, 2016, Keith Lamont Scott, a 43-year-old African American, was shot and killed by a police officer in Charlotte, North Carolina. Police were at his apartment complex seeking another individual when they encountered Scott, who was sitting in his car waiting for his son’s school bus. Believing him to be utilizing illicit materials and to have a firearm, Scott was asked to get out of the vehicle and was shot while exiting and walking backwards.

Stories of black men losing their lives at the hands of law enforcement are all too

familiar in America today. Charlotte is no exception. Three years before Scott was killed, a similar incident took the life of 24-year-old Charlotte resident and Florida A&M football player Jonathan Ferrell. For our city, Scott’s death was a painful reminder that police brutality is still pervasive. Weeks of protests and fraught emotions ensued. One person was killed and multiple officers and civilians were wounded in the unrest.

In these situations, a sort of shock and paralysis can take hold of communities. While some protest, many others stay indoors. Businesses shut down. As a result, there are few safe spaces to process what is happening, allowing divisions and feelings of anger and fear to fester. As a staff, we at Levine Museum of the New South decided to change this by taking immediate steps to address the incident and provide a place for people to talk and be supported as they struggled to heal and negotiate the future in a city where so many divisions exist. In the weeks following the shooting, we offered a number of events, including tours and a talk-back with community members, a town hall-style program “Where do we go from here?” with staff historian Dr. Brenda Tindal, and a week-long Twitter forum.

But the initiative that required the most of us as an institution was a rapid-response exhibition on the subject. We had been working on a related project already that looked at broader community responses to police brutality, but we knew that capturing Charlotte’s particular story while  it was still so present in people’s hearts and minds was going to require a renewed sense of flexibility and courage on our part. We also knew it was integral to helping the community heal.

it was still so present in people’s hearts and minds was going to require a renewed sense of flexibility and courage on our part. We also knew it was integral to helping the community heal.

Our goal for the exhibition was simple: to show visitors that the current situation is complicated, that multiple perspectives exist, and that historical context matters. To do this we needed to present a broad range of narratives. Kate Baillon, vice president of exhibitions, reached out via her personal social media channels to crowd-source stories, images, videos and audio; asking contacts to push requests out to their friends and followers on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. She also conducted in-person interviews and forged valuable partnerships with the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Johnson C. Smith University to create archives for digital and physical materials, which ensured that the items were held in the public trust and remained accessible. This methodology garnered narratives from a public defender, medics, protesters, media, activists, a police officer and clergy.

But the perspectives were not complete. Eliciting broad responses from elected officials, law enforcement and uninvolved downtown residents was not successful. As the Museum pushed toward the first production deadline, we knew there were significant holes in the exhibit and that we would have to adjust our strategies to address them. This led us to do something we hadn’t done before: agree to open the exhibit although it was effectively not ready, and add to it as we received more stories and perspectives. We were a nation, a city and an exhibit in progress.

But the perspectives were not complete. Eliciting broad responses from elected officials, law enforcement and uninvolved downtown residents was not successful. As the Museum pushed toward the first production deadline, we knew there were significant holes in the exhibit and that we would have to adjust our strategies to address them. This led us to do something we hadn’t done before: agree to open the exhibit although it was effectively not ready, and add to it as we received more stories and perspectives. We were a nation, a city and an exhibit in progress.

To ensure that the stories that we did have were presented correctly, however, we needed an approach that did not privilege one narrative. Museum leadership, exhibit and education staff reviewed the materials and marked which stories met the exhibit goals and were the most impactful to them. The passages with the most endorsements were used as “quote panels.” In this manner, everyone’s voice on the team held the same weight and the resulting exhibit content revealed a variety of vantage points. Ensuring everyone  had a part in the process was absolutely necessary to build consensus, ensure authenticity and buy-in.

had a part in the process was absolutely necessary to build consensus, ensure authenticity and buy-in.

But it was time-consuming. With the opening date already publicized, we were still not ready. This was another daunting challenge that ultimately provided an opportunity for more engagement. (The message here is clear: As museum officials, never give up!) We used the publicized opening in December as a chance to prototype the exhibit and host a listening session with the Board of Directors, community members and exhibit contributors. We asked for reactions, for what was missing, for what people wanted more of or less. The majority of the feedback was positive, but some wanted more continuity in our timeline and more voices, including those of the “establishment” and law enforcement.

In an exhibit about such a contentious topic, the prototype gave us an opportunity to gauge the appetite for discussion around the issues related to policing and protest. Wanting to create more distinction between the typical “museum voice” and the community conversation, we reconfigured the exhibit. Originally, we began with a timeline, followed by a photography section that looked at national protests and then narratives of those killed in police custody, before ending with Charlotte’s response. In the end, we reversed the last three sections, moved walls, removed a large chunk of the early timeline – essentially reimagining how visitors would engage with the content of the exhibit. By this time, it was also decided that no charges would be filed in the Scott shooting. As the community grappled with the case’s development, it seemed to open the door for police officers and law enforcement officials to share their experiences. The museum reached out to them again and stories flowed in.

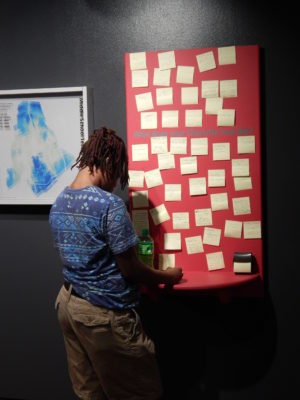

“K(NO)W Justice K(NO)w Peace” opened successfully in February 2017 – just a  few months after Keith Lamont Scott was killed. For staff, it required more flexibility and compromise than most exhibitions, but the end result has been both moving and revealing. The exhibit is a collection of diverse stories, but also one that integrates the history of Charlotte into these present day experiences. A timeline looks at how economic disparities are created and reinforced along racial lines by structural policy decisions, both locally and nationally, in education, housing and law enforcement. An interactive map display allows visitors to layer maps over one another to see how low performing schools, income inequality, the racial make-up of neighborhoods and officer involved fatalities correspond to one another.

few months after Keith Lamont Scott was killed. For staff, it required more flexibility and compromise than most exhibitions, but the end result has been both moving and revealing. The exhibit is a collection of diverse stories, but also one that integrates the history of Charlotte into these present day experiences. A timeline looks at how economic disparities are created and reinforced along racial lines by structural policy decisions, both locally and nationally, in education, housing and law enforcement. An interactive map display allows visitors to layer maps over one another to see how low performing schools, income inequality, the racial make-up of neighborhoods and officer involved fatalities correspond to one another.

We also continue to engage the community through a Book and Film Club series on officer-involved shootings and protests. With author talks, virtual conversations and in-person meetings, the goal is to continue to bring a variety of people in the community into the same space so they can talk across difference and build a growing understanding of the complexity of the issues. In coming together, we construct bridges but also shine a light on how much divides us. While the exhibit has been lauded by most of those who have seen it for the context and content, there have been several people who have expressed their refusal to view the exhibit. In their statements  on social media and to staff, they wrongly pre-judge the exhibit as anti-police merely because of the topic it explores. The continuing work – be that community dialogues with civic groups, tours, talks, historian-led programs, or art in the community – is finding the entry points to invite the Charlotte community to “come to understand” not only what has happened but how we move forward.

on social media and to staff, they wrongly pre-judge the exhibit as anti-police merely because of the topic it explores. The continuing work – be that community dialogues with civic groups, tours, talks, historian-led programs, or art in the community – is finding the entry points to invite the Charlotte community to “come to understand” not only what has happened but how we move forward.