Old Sturbridge Village, located in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, is one of the nation’s oldest living history museums and the largest outdoor living history museum in the northeastern United States. Since opening in 1946, the Village has depicted life in 1830s rural New England through exhibitions, public programs, and educational offerings to an audience of more than 21 million visitors. In preparation for the Village’s 75th anniversary, the museum’s leadership has established a Five Year Vision that will help the institution take its core elements — interpretation, collections and research, education, and preservation — from good to great as part of an institutional commitment to the public, living history. We want each visitor to find meaning, pleasure, relevance, and inspiration through the exploration of history.

museums and the largest outdoor living history museum in the northeastern United States. Since opening in 1946, the Village has depicted life in 1830s rural New England through exhibitions, public programs, and educational offerings to an audience of more than 21 million visitors. In preparation for the Village’s 75th anniversary, the museum’s leadership has established a Five Year Vision that will help the institution take its core elements — interpretation, collections and research, education, and preservation — from good to great as part of an institutional commitment to the public, living history. We want each visitor to find meaning, pleasure, relevance, and inspiration through the exploration of history.

You are currently working with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience on a multi-year project to begin the process of broadening and deepening your interpretation to include questions of labor, race, and gender. Can you speak about your decision and process as an organization to reinforce or grow your focus on these experiences?

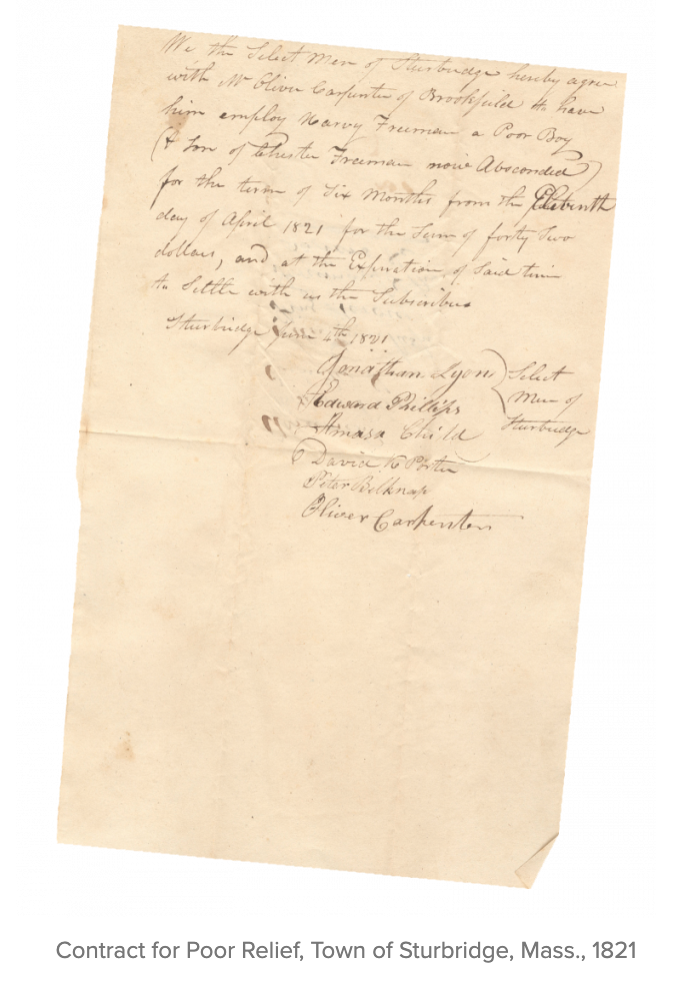

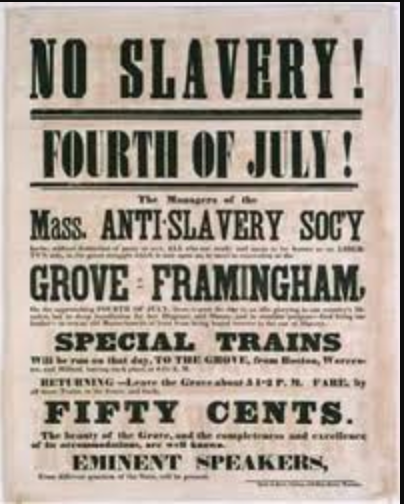

Old Sturbridge Village has taken pride in representing the daily life of 1830s inhabitants in a rural New England town, but it has often struggled to tell a complete story, especially when it comes to stories of minority populations and non-conformists. In some respects, the Village’s interpretation of “average” life has resulted in an unintentional flattening of history, when in fact, the half-century from 1790 to 1840 represents a transitional time when New Englanders were caught between abolitionist movements and deep-seated racism, surrounded by advances in women’s freedoms as well as long-standing societal expectations of [traditional] gender roles. We want to make sure that that societal complexity is addressed with our visitors, both as a way to dispel the myth of the past being a simpler time and to connect to the complexity of people’s lives today.

Much of your work with Sites of Conscience has focused on deepening your use of dialogue in your programming to help visitors reflect not only on the history presented but also their own relationship to it. Can you say a bit more about this experience and what new opportunities this approach has opened up for staff and visitors?

As a museum that focuses its interpretive approach on third-person interpretation, we have always felt that conversation and dialogue with our guests provides a far richer learning experience that allows us to connect history to the everyday lives of our visitors. Museum staff [who are] actively involved in the creation of training materials for their exhibits and programs are often the most committed to dialogic interpretation, rather than mere recitation of the history. As a result, we have engaged staff in working collaboratively to develop new training materials for exhibits that they either oversee or interpret daily. By giving the entire staff ownership over how the history is presented, it becomes easier to capture their passion for their work and harness that for deeper dialogue with our guests. The trainings with the Coalition have provided guidance as we assemble a tool kit for staff to make those visitor interactions even more meaningful.

Can you say a bit about the challenges and opportunities being a living history museum presents? How have the strategies you learned with Sites of Conscience helped you to navigate and maximize these respectively?

One factor of being a living history museum that is both a challenge and an opportunity is the fact that we are trying to recreate a lived environment that in many ways is foreign to our visitors today. Our staff dress in replica clothing from the 1830s, the buildings are different from those we live and work in today, things smell differently, etc. These can certainly be jarring to our guests and at times make it difficult to engage with them. However, the beauty of dialogic interpretation is that all of those features of our work that separate us from our visitors can also be used as hooks to draw them into deeper discussions and result in shared learning. While we may not be able to recreate every element of life and the past, and in many cases should not strive to, the tools that we have acquired through our trainings with the Coalition will help us to give visitors a more complete and inclusive sense of the past and hopefully feel that they are part of a community when they are here.

You broach an important point by mentioning that sometimes we should not strive to recreate every element of the past. Can you say a bit more about how you make those decisions – about what to recreate and what not to recreate? Are there any strategies you can share for how to present issues related to injustice, race, and gender with both honesty and sensitivity?

To speak to your point about what history we decide to recreate and what history we choose not to recreate, it all comes down to meaningful learning objectives. We want to make sure that every program we present to the public strives to make the public feel welcome and actively engaged in learning about history. As a site focused on third-person interpretation, we’re not trying to have visitors pretend that they are actually in another place or time. Instead, we focus on providing context for the history through dialogue, which is especially useful when discussing race and gender in the period.

Finally, can you share one fact about this time and place in history that may not be found in an average school textbook but is integral to gaining a deeper understanding of how issues related to race and gender justice shaped American history in towns like Sturbridge Village?

An important fact that is integral to gaining a deeper understanding of how issues related to race and gender justice shaped American history in towns like Sturbridge Village is that social reform was really becoming a major societal movement starting in the 1820s. From anti-slavery work to advocating for temperance, many New Englanders looked to improve their society as they sought to create what was, in their mind, the model of a republic. It was these movements that gave more of a voice to the Black community and women and that growing influence and would be used to push for further social change in the decades to come.