As part of its new initiative, From Brown v. Board to Ferguson: Fostering Dialogue on Education, Incarceration and Civil Rights, the Coalition is bringing together 11 Sites of Conscience from across the US to implement programs that train youth and others to be active leaders on issues of race and education equity in their neighborhoods.

In the following essay – part of a blog series that showcases the participants’ programs – Hakim Bellamy, the Inaugural Albuquerque Poet Laureate, writes about a dialogue he co-facilitated with the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Through the Coalition’s From Brown v. Board to Ferguson project, Sites of Conscience are acting as alternative safe spaces for many people of color, providing opportunities for them to voice their experiences and learn to become effective advocates for education equity.

As we developed our first dialogue program for the project, it was important for the team at the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) to reach those most affected by this so-called “school to prison pipeline.” We found them in 11 female inmates from the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center outside Albuquerque, New Mexico. All were enrolled in a GED program to obtain their high-school equivalency degrees, so we knew that each had a unique story to tell about the subject of incarceration and education. The fact that they were women also appealed to us, as most programs that come to the jail cater to the male population, which we thought was unjust. In the end, we ensured a diverse composition of women who showed palpable interest and would be “in” long enough to participate in the program, which included four workshops over six months. In other words, the selection was very intentional. And from day one we knew the group was perfect.

As we developed our first dialogue program for the project, it was important for the team at the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) to reach those most affected by this so-called “school to prison pipeline.” We found them in 11 female inmates from the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center outside Albuquerque, New Mexico. All were enrolled in a GED program to obtain their high-school equivalency degrees, so we knew that each had a unique story to tell about the subject of incarceration and education. The fact that they were women also appealed to us, as most programs that come to the jail cater to the male population, which we thought was unjust. In the end, we ensured a diverse composition of women who showed palpable interest and would be “in” long enough to participate in the program, which included four workshops over six months. In other words, the selection was very intentional. And from day one we knew the group was perfect.

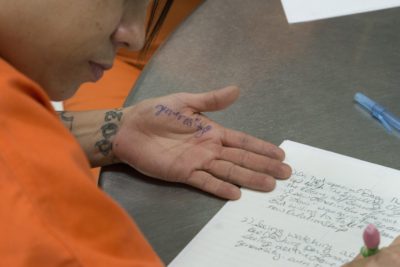

From the very first workshop, described here, we made it a point to meet them, to learn about their aspirations, not their alleged infractions. For us at MOIFA, this is the first step to becoming an effective activist – knowing that your story matters, and knowing that when fleshed out, personal narratives can be extremely useful in conveying to others the true impact of discrimination on everyday lives. We did this by asking reflective questions, ones that turned their gaze inward, questions like, “What did you want to be when you grew up?” No one says they want to be incarcerated when they grow up. At least not at first – not until they are taught to want it because wanting anything else is unrealistic. While the inmates’ stated dreams were different in detail, they were aligned in theme. All the women wanted to make a difference. And after first drafting some community agreements, we began to take the next step: sharing their stories and building relationships in order to help them make those dreams come true.

an effective activist – knowing that your story matters, and knowing that when fleshed out, personal narratives can be extremely useful in conveying to others the true impact of discrimination on everyday lives. We did this by asking reflective questions, ones that turned their gaze inward, questions like, “What did you want to be when you grew up?” No one says they want to be incarcerated when they grow up. At least not at first – not until they are taught to want it because wanting anything else is unrealistic. While the inmates’ stated dreams were different in detail, they were aligned in theme. All the women wanted to make a difference. And after first drafting some community agreements, we began to take the next step: sharing their stories and building relationships in order to help them make those dreams come true.

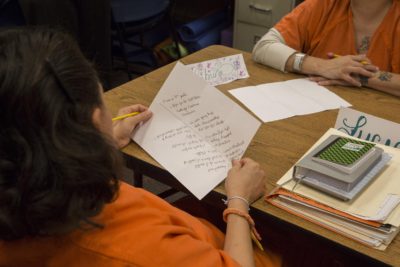

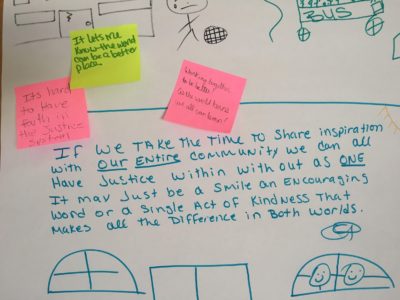

Using visual folk art that we brought to the detention center, we started to build a shared vocabulary for reflection and the exchange of ideas. These are essential tactics and skills the women can use as they think about how they can affect their communities and even become advocates for change one day. Along the way, we asked the participants questions like, “Does this artwork make you think about your own story or experience of growing up and struggling to be the person you want to be?” The goal was to show them how to use art and other means to reach those you do not necessarily know and find common ground.

one day. Along the way, we asked the participants questions like, “Does this artwork make you think about your own story or experience of growing up and struggling to be the person you want to be?” The goal was to show them how to use art and other means to reach those you do not necessarily know and find common ground.

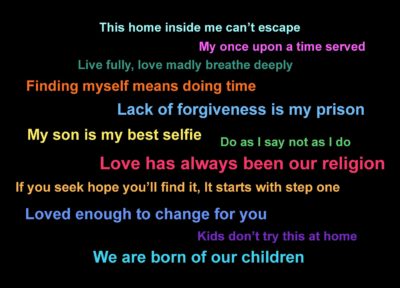

We ended that first visit with Six Word Memoirs – which are exactly what they sound like and,

we hoped, would be a way for the women to bookend all we had discussed in our time together – a little micro-poetry technique for their toolbox. Already master storytellers, they wrote things like, “Lack of forgiveness is my prison” and “This home inside mecan’t escape.” We also wrote some as a group, including “Changing lives from the inside out.”

Over the course of the four workshops, the women taught us plenty as well – particularly about the challenges people face getting ahead in the world today. We talked about home and homelessness, and about school, prison and everything in between. Sharing their stories not only let the participants know they were not alone in their struggles, but showed them how listening to others, extending empathy to others, can lend itself to positive, collective action. “I learned active listening. I am aware now more than ever how important it is to listen,” explained one participant. As facilitators, we listened to their powerful stories too, and hoped that one day these women could transport them to the community beyond the walls around them.

Over the course of the four workshops, the women taught us plenty as well – particularly about the challenges people face getting ahead in the world today. We talked about home and homelessness, and about school, prison and everything in between. Sharing their stories not only let the participants know they were not alone in their struggles, but showed them how listening to others, extending empathy to others, can lend itself to positive, collective action. “I learned active listening. I am aware now more than ever how important it is to listen,” explained one participant. As facilitators, we listened to their powerful stories too, and hoped that one day these women could transport them to the community beyond the walls around them.

A similar version of this essay appears on the Museum of International Folk Art’s website here.